Just less than three years, a young farmer by the name, Kofi Darko who lives at Akrpong in the Eastern region decided to venture into farming. It was not an easy decision to make. Agriculture is generally regarded as a high-risk economic activity in Ghana. Financial institutions are reluctant to offer financial supports given the precariousness of the business.

“I went to different banks to apply for a loan, but all of them turned me down,’’ Mr. Darko, who is hoping to expand his five-acre pineapple farm subtly said.

The main reasons why the banks have been reluctant in lending to the agriculture sector include high-risk perception of the sector, lack of adequate risk management tools, and existential risks such as diseases, pests, and changes in climatic factors.

Smallholder pineapple farmers are predominantly located in the Central, Eastern, Greater Accra, and Volta regions in Ghana—the ecological zones known for growing the fruits but over the years lack the needed capital to produce on a commercial basis.

Most smallholder farmers living in rural communities have limited access to financial services like savings accounts. As a result, 36% of farmers in Ghana save their monies at home. According to GSMA, only 20% save their money in a bank and 28% save their monies on a mobile money wallet. Others save with village institutions, credit unions, and ‘susu’ (small personal savings) collectors.

Formal institutions like banks are unable to access this information to understand the economic activities of a farmer who is usually regarded as high risk. As a result, Farmers usually secure loans from other informal sources like friends, purchasing clerks (who are also usually farmers), money lenders who charge high interests rate.

“The banks usually informed me that my farming business, even though it looks promising, there is no guarantee that I can repay the loan. I felt that this is not right and even thought of changing my mind,’’ Darko emphasised.

“The banks do not help us because I think they have done some before, and the farmers have failed them, therefore as a farmer applying for a bank loan is usually unsuccessful. The local market is not reliable somehow—it can be that today pineapple sells at the cost of 2.50 cedis, the following week the price reduces to 1.50 cedis, so the bank looks at the fluctuations in prices and decides that if they give you money to do business, the farmer cannot pay back the loan,” says Mr. Emmanuel Appiah, a pineapple farmer and a beneficiary of the drone and precision agriculture project.

However, Emmanuel Appiah, farmer at Nsadwi in the Komenda-Edina-Eguafo-Abbrem (KEEA) district has now found immense hope in technology courtesy of drone and precision agriculture to transform his production level to a higher level. The Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension of the University of Cape Coast and partners are assisting smallholder farmers with relevant and real-time information on the pineapple production process required by farmers to produce varieties that are important for the market and in the most productive way.

Drone technology is providing farmers with reliable information based on the farmers’ own land and crops’ requirements to optimize crop production, produce high-quality fruits, minimize production cost, and meet consumer preferences.

“Since I started the programme it has given me more knowledge. Two or three years ago, I had about two or three acres but now only this year, I have planted 6 acres of pineapples and looking forward to expanding even further,” Appiah mentioned.

“If I harvest 2000 fruits of a good size, I can get 3000 cedis and I use that to cater to my family and that is why I am expanding my farm this year,” he added.

The problem of marketing for Emmanuel Appiah’s pineapples has been addressed by the project, thus, the farmer now sells directly to HPW Fresh & Dry Ltd. located at Adeiso 70 km from the capital, Accra. The company is the largest producer of naturally dried mango, pineapple, and whole coconut in West Africa, processing over 20,000 tons of fresh fruit, exporting 2,000 tons of dried fruits.

Instead of relying on extension officer visits and low returns from informal pineapple traders, an information system has been established to link farmers to production and market information – and to each other. The system uses drones (small, unmanned aircraft) that provide feedback information on crop health, performance, and yield estimates and then relay this through a mobile phone platform linking farmers to extension agents, markets, and the university.

“Since we started to sell our product to HPW Fresh & Dry Ltd, I can say that it is far better than the local market. Since I started pineapple farming in 1990, what I get from the company HPW is higher than what I sold to the local market,” Appiah says.

According to him, the project has offered great knowledge in terms of record-keeping, plastic mulch, application of inputs, planting in rows, planting pineapples in intervals, all helping to increase the yield on his farm.

He said that the project has been a lifeline to their economic activity and helping farmers to have a decent living and eventually helping to cater for their households.

“Our pineapples are now directly sent to the market via HPW without any transportation difficulties. At first, we did not have any company to sell to and that created a lot of problems as the post-harvest loss is a concern, but now things are getting better since I have ready markets for my produce,” Mr. Nyame, at Nsadwir said.

“In the past, we did not know anything about nursing of pineapple but due to the project, we now do, and that is helping us to do the right things on the farm which will eventually improve the pineapple production in the long term,” he said.

“Currently, we have access to land for pure organic production of pineapples which will help us to get even more profits to promote our standard of living,” he stated.

He mentioned that since the project seeks to establish a factory, it will help the farmers to deal directly with the team and also not focus solely on pineapples production but also other fruits.

Mr. Zikiru Shaibu, a Ph.D. student who is working on the project said that the project has exposed farmers to market opportunities, therefore, if they should produce more of the pineapples, they would get more income.

“They are making more yields now, they are having good prices which means their income is increasing leading to increase of farm size, getting premium money to support themselves and their families, he said”

To Shaibu, the farmers’ knowledge development in terms of using the right agro-inputs like pesticides, fertilizer, how to use the application schedule, all these knowledge resources have improved. Now they have knowledge on some of the pineapple varieties we have, not only what they grow but new ones to adopt.

Sustainability of the project.

Mr. Zikiru Shaibu is specializing in agricultural extension and ICT indicated that the project looks at not only focusing on pineapples production but the entire value chain from inputs, through production, processing, and then marketing, until it even reaches even the consumer.

The project off-take farmers’ products and sell them. We are establishing a processing plant for value addition. The processing plant is at the production stage and we are using drone technology, and mobile phones to enhance productivity. Sustainability wise things being put in place like machines, and other resources to continue with the project. After the project, we would still continue with the activities.

The project is designed in such a way that the farmers would be supported with some materials to establish their own farms so once the project ends, there would still be produced for the market.

Even though the government of Ghana’s new initiative—Planting for Food and Jobs seeks to contribute to the modernization of the agriculture sector, thereby leading

to the structural transformation of the national economy through food security, employment opportunities, and reduced poverty, there are many challenges to agriculture, such as climate change, lack of access to input and markets accessibility; lack of basic infrastructure in rural areas, lack of extension services, and the lack of research and development facilities.

The major challenge with sustainability is the technology or inputs, like tractors. There are limited tractors in the central region and the farmers do not get access to them when needed. There are some simple tools that are not available in the country unless there is a collaboration with the Chinese to develop it for you.

Project in perspective

Most of the smallholder farmers producing pineapple variety named “Sugar Loaf” mainly sells at the local market and at low prices, leading to low income. The situation makes pineapple cultivation unattractive. Meeting the demands of the export market and agro-processing industries is one way for smallholders to increase their income level and improve their livelihoods.

The project is therefore using drones and precision agriculture to assist farmers in upscale their pineapple production.

“Aerial views and advice based on index maps generated using drone technology enabled them to be more effective and efficient in managing the farm and ensure improved plant growth and higher yields,” says the principal investigator, Festus Annor-Frempong.

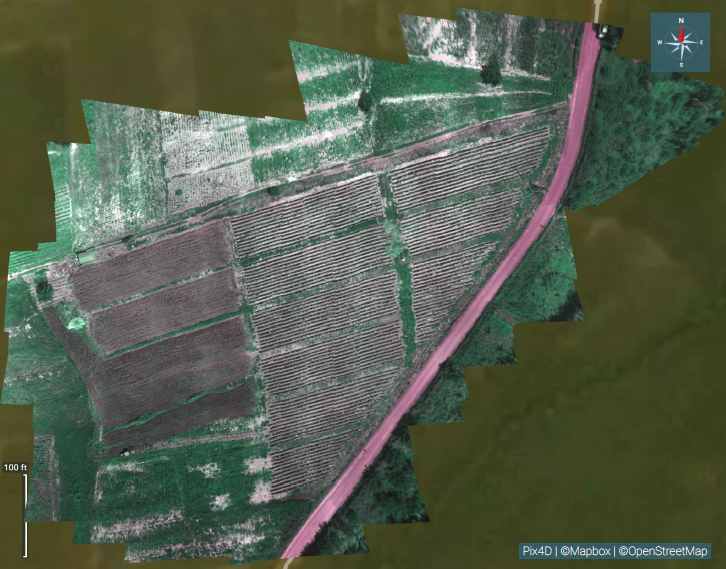

The drone, a Parrot Bluegrass, was used to map the demonstration plot and also captured initial relevant agronomic data of the crops on the field. The map enabled farmers to appreciate the shape and size of the demonstration plot.

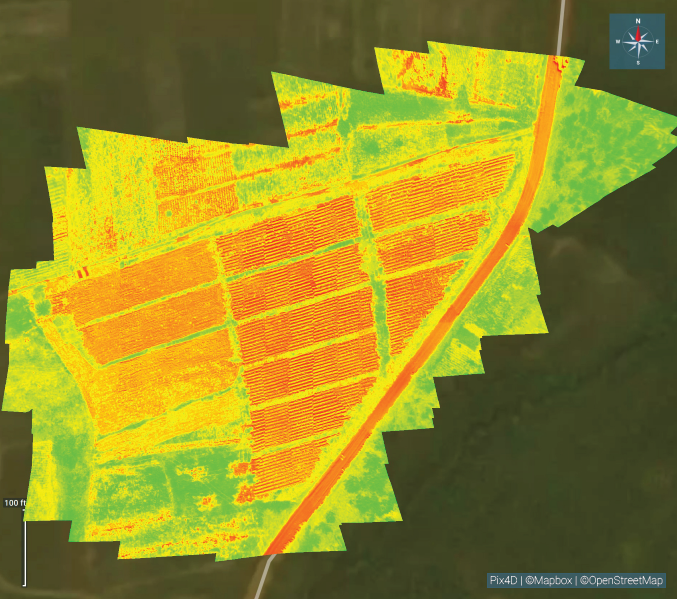

The sensors of the drone collect multispectral and Red, Green, Blue (RGB) imagery of the pineapple crops. The captured imagery was processed to generate index maps. These index maps showed the chlorophyll content of individual pineapple plants which were used to estimate the nutrient requirement of plants and provide recommended fertilizers to be applied by the farmers.

Improving farmers’ knowledge and situations.

The project team measured the impact of drone technology on farmers’ livelihoods in terms of crop performance which is likely to generate more income and changes in competencies in pineapple production. The experience with farmers with respect to the management of the demonstration plot prompted the team to share knowledge on principles of precision agriculture with the farmers. Farmers learned about the type, quantity, and effect of various elements in a fertilizer and pesticide application, and the need to use these agrochemicals effectively and efficiently without causing harm to the environment.

RGB composite image of pineapple fields

NDVI index map of the same fields

From the RGB images and index maps developed using multispectral imagery, smallholder farmers were able to gain an enhanced bird’s eye view of the demonstration plot. The group discussions helped farmers to discover the relationship between land size and the crop density, land size, and the number of agrochemicals required, and the costs involved in the production of a particular area. The map from the drone technology demonstrated the importance of having clear plot boundaries to prevent conflicts and disputes with neighbours as well as optimization of land use. Hitherto, the traditional process of determining plot boundaries was not as precise, usually being orally transmitted, and depends on the location of natural boundaries such as trees and stumps.

Moreover, the map and size of the demonstration plot from the drone technology enabled farmers to plan various road paths, and the number of ridges to construct on the plot. The pineapple farmers proved to be knowledgeable and well informed in crop husbandry. Farmers were in the position to prepare the land properly to allow the soil to retain sufficient moisture for plant growth and used a bed height of about 20 centimeters with a breadth of one meter, and a length of 100 meters to improve drainage.

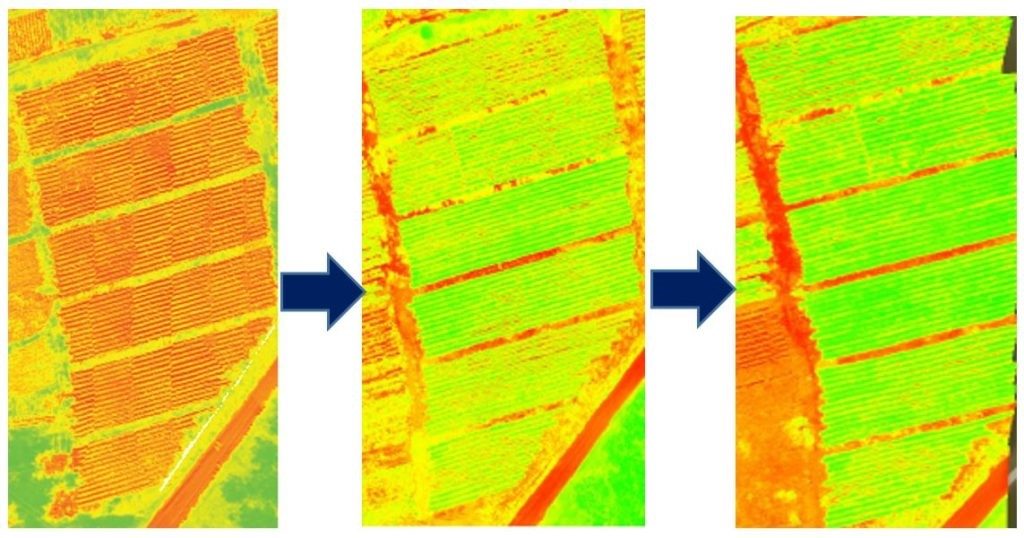

The Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) maps showed significant changes in the growth of the pineapple plants months after the application of various agronomical practices. The applications were dependent on information from previously obtained NDVI index maps of the demonstration plots. Farmers subsequently planned on the appropriate and adequate usage of agrochemicals based on the colour bands of the NDVI index maps. The different colours on the map signify the health status of the pineapple. For instance, the red colour shows poor-performing crops, yellow coloration shows an intermediate performance, and green colour shows healthy crops and better (expected) yields.

The farmers understand that the red areas on the index map need more attention when applying fertilisers or pesticides. The use of agrochemicals in this way became demand-driven and characterized by location and specific application. Farmers anticipate high yield from the demonstration field as the time sequence of index maps demonstrate a positive change in pineapple growth in response to geo-located crop husbandry practices applied by the farmers.

Precision farming advisory based on drone technology has brought about an improvement in land use and crop performance. More importantly, farmers have developed specific skills and acquired knowledge of innovative technologies for agriculture. For them, it has not necessarily become easier to grow pineapples, but the field’s productivity has improved thanks to acting based on real-time drone-tech generated advice. This confirms that at least in some aspects, drone technology could improve the livelihoods of smallholder pineapple farmers.

“It is a great opportunity given to KEEA farmers to explore as far as modernization of agriculture is concerned. Times and trends are changing and the earlier you adapt to the change, the better for your development. Today, there are a lot of modern techniques ….You require up-to-date information….. I wouldn’t need to pick a vehicle to deliver information to you, today, mobile phones have come to save this great deal. We can now exchange information with ease,” says the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) Director for KEEA, Mrs. Victoria Dansoa Abankwa.

The project is led by the Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension of the University of Cape Coast, with the support of the Technical Centre for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation ACP-EU (CTA), the MasterCard Foundation, and the Regional Universities Forum for Capacity Building in Agriculture (RUFORUM). The project started in 2018 and ends in 2021.

This story was produced as part of the Africa 21 Media and Journalism in Africa Days 2020: Climate change in anglophone Africa

Written by: Samuel Hinneh