To reach maximum yields, it is important to know where to start from, and how to start it. With that in mind, this is how one can maximize soybean yield today to reach the next level.

Understand Your Mission.

“A soybean producer’s job is to use the big three factors that produce yield — light, water, and nutrients,” says Farm Journal Field Agronomist Ken Ferrie. “How you capture and manage each factor affects the three components of yield: pods per acre, beans per pod, and the size of the beans.

“Pods per acre correlates to nodes per acre and plants per acre. But, while plants and nodes per acre are important, they are less significant than with corn because soybeans quickly adjust growing factors to their environment.”

Plant the Right Population

“You need enough plants and nodes per acre to support the number of pods necessary to hit your yield goal,” Ferrie says. “You need enough vegetative growth to capture all the available sunlight and to close the rows. Row closure minimizes water loss to evaporation and aids in weed control.”

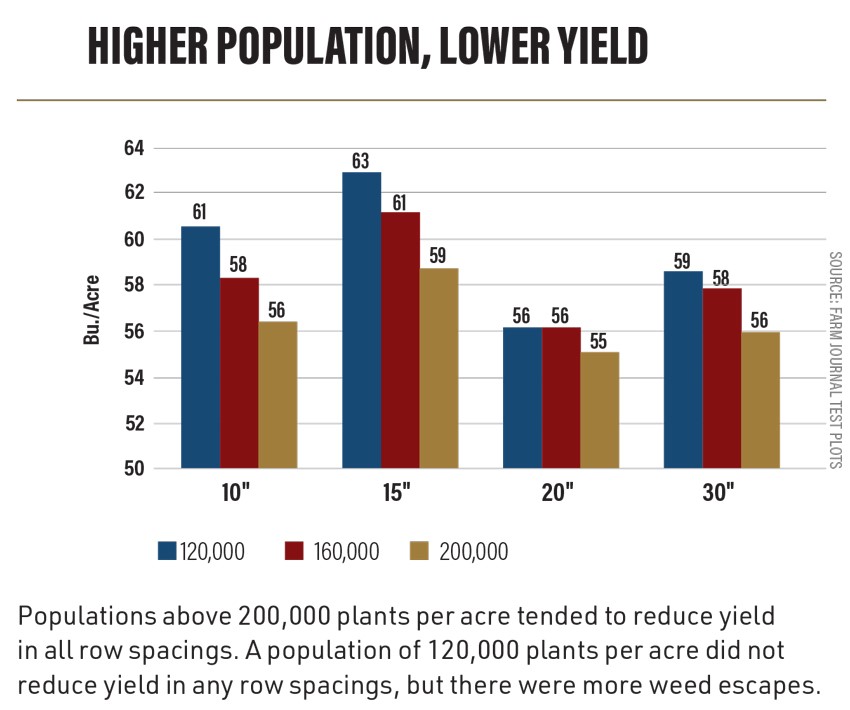

One of the longest-running Farm Journal Test Plot studies tracks population and row spacings ranging from 120,000 to 220,000 plants per acre in 7½”, 15″ and 30″ rows. “We’ve learned varying population from 120,000 to 220,000 plants per acre had little effect on yield most years,” Ferrie says. “Narrow rows did not respond to higher populations.

“Pushing population above 200,000 plants per acre tended to reduce yield in all row spacings,” Ferrie continues. “A population of 120,000 plants per acre did not reduce yield, although there were more weed escapes, especially in 30″ rows. Based on yield, the data suggests 120,000 plants at harvest is adequate to maximize yield. Higher populations produced more nodes than we were able to fill.”

The same study revealed a yield advantage of 3 bu. to 5 bu. per acre for 7½” and 15″ rows versus 30″ rows at the same population. Ferrie attributes the narrow-row yield advantage to better water use and light capture.

At 120,000 plants per acre, weed control was noticeably better in narrow rows than wide rows, Ferrie notes. He attributes that to faster canopy closure.

Rolling Plants Can Boost Yield, But Timing Is Crucial

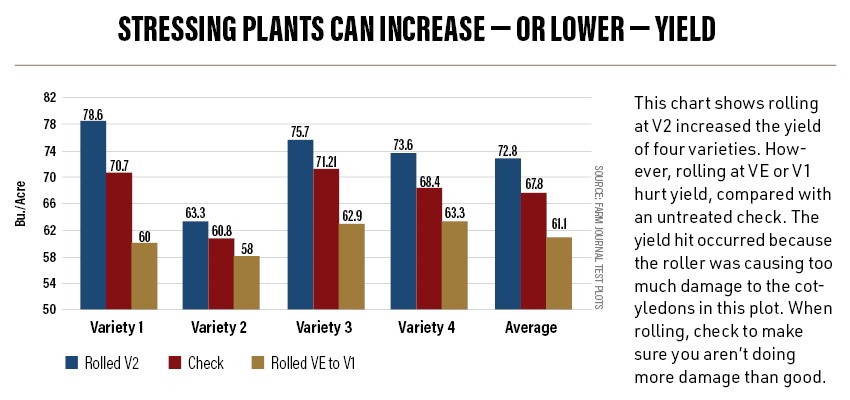

Rolling with a land roller (normally done to keep rocks out of combines) and applying certain herbicides can stress soybean plants, causing them to respond with more branching, which results in more nodes.

“Rolling plants at the V1 to V3 stage, we saw a 2-bu.-to-5-bu.-per-acre yield increase, but we also found 1-bu.-to-3-bu. yield decreases,” Ferrie says.

“If you roll too early, at VE (emergence), you can break the plant’s neck (the hypocotyledonary arch) or knock-off cotyledons,” he adds. “The cotyledons provide the food supply for plants through V1. At the V3 stage, the plants can become too brittle to roll; they will break off below the first growing point.”

To stimulate branching, the sweet spot for rolling turned out to be the V1 or V2 growth stage. “But even in the sweet spot, you must consider daily conditions for each variety in each field,” Ferrie says. “Sometimes in the morning, plants are more brittle and likely to break, but they can be rolled later in the day.”

Before you roll a field, step on some soybean plants and see if they spring back or break off. “If they break, they are too brittle to roll,” Ferrie explains. “When you roll soybeans, check to make sure you aren’t doing more damage than good.”

As with rolling, timing is the key to promoting branching by applying herbicides. “When you apply a herbicide that tends to burn soybean leaves, such as diphenyl ether, it triggers a defense mechanism that causes the plants to add branches,” Ferrie says. “In our test plots, we saw increases up to 5 bu. per acre.

“The time to stimulate branching and increase yield is typically the late vegetative to early reproductive stages. If you apply the herbicide during late flowering and early pod set, the stress it produces might cause flower and pod abortion.”

Soybeans Respond More to Soil versus Applied Fertility

“Keep soil nutrient levels in the optimum range, especially pH,” Ferrie says. “Acid and alkaline soils give soybeans trouble.”

For soybeans to produce their own nitrogen, rhizobia bacteria must be present in the soil. “Fields void of soybeans for two or more years tend to respond to seed inoculants,” Ferrie says.

Protect Against Pests

“In our Farm Journal Test Plots, we see some of the biggest responses to insecticide when we are able to stem off insects when plants are already stressed by weather,” Ferrie says. “Actually, we are not seeing a yield response — we are reducing the loss.”

With water molds, tests show seed treatments can increase emergence and improve stands. “In wet years, they can be the difference between keeping the existing stand and replanting,” Ferrie says. “With increased emergence, you might find you can plant 130,000 seeds, rather than 150,000, to get a stand of 120,000 plants. It was difficult to get a consistent yield response from seed treatments, but we saw better emergence almost every year.”

The Rules Change with Late Planting

“When soybeans are planted late, they reach the R5 stage faster and stop growing. Shorter plants have fewer nodes per plant,” Ferrie says.

In that situation he recommends more plants, so pushing up population and narrowing rows is more important. In late-planting studies, narrow rows responded better at 160,000 plants per acre than at 120,000, and 30″ rows responded to population increases all the way to 200,000 plants per acre.

“Unlike corn, where you shorten maturities for later planting, you want to stay the course with soybeans or even lengthen your maturities,” Ferrie explains.

”Flowering is influenced more by night length than planting date. Plants stop growing at R5, so if you shorten the maturity, you risk having short plants.”