The exacerbation and ramifications of the Russia-Ukraine crisis might be catastrophic, while the ripple effects could spread across a world currently recovering from pandemic supply chain disruptions. Grains, potash, metals, wood, and plastics—all of which are utilised in a wide range of products and by several businesses, from fertiliser producers to automobile manufacturers—are among Russia’s most important exports.

When two elephants fight, the grass suffers, according to a well-known saying. As of yet, the crisis’ impact on global trade has been most pronounced in the Black Sea, where Russian and Ukrainian ports serve as significant hubs for wheat and maize exports. As a result, the world’s second-largest grain exporting region has been practically closed down. It will take time to increase grain supplies and the sheer volume that could be diverted as a result.

Ukraine accounts for 16 % of global maize exports and 30 % of wheat exports which means developing countries that rely on imports could face major supply shocks due to the conflict and sanctions on Russia. For instance, Egypt, India, and Turkey; all these countries rely significantly on Russia for everything from flatbread ingredients to natural gas and tourism, making them particularly vulnerable.

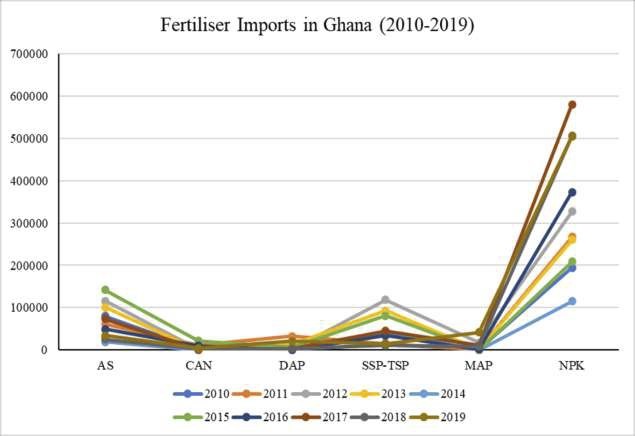

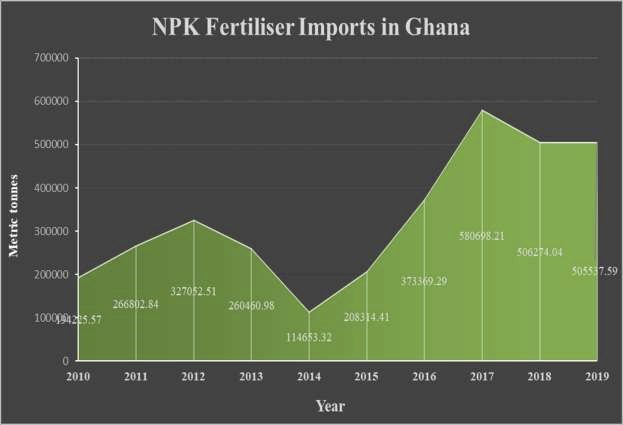

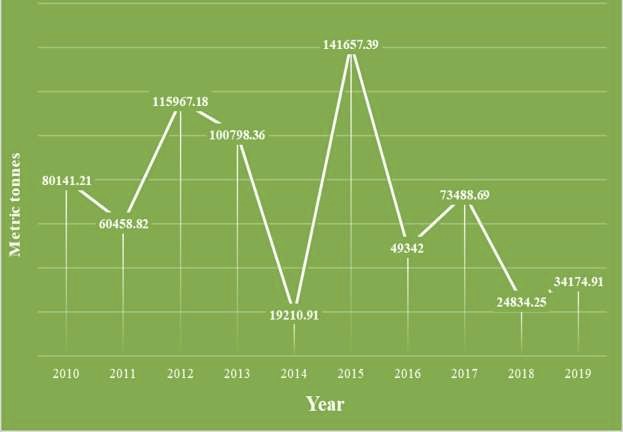

Ghanaian farmers in particular rely on inorganic fertilisers imported from Europe for food production. Ghana imported 425.1 thousand metric tonnes of fertilisers in 2019, up from 315.2 thousand metric tonnes in 2018 (Statista, 2018). Fertiliser imports in 2017 were 444.2 thousand metric tonnes, the highest level ever. The most commonly imported fertiliser type into Ghana is nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium (NPK) fertiliser. With an annual output of 10.4 million metric tons, Russia ranks fourth in the world for nitrogen fertiliser production (NationMaster.com, 2019).

Russian natural gas reserve is roughly 47, 805 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2022 and Russia is the world’s top natural gas producer, exporting approximately 196 billion cubic metres of gas each year (World Population Review, 2021). Chemicals, fertilisers, hydrogen, and a slew of other things rely on the world’s gas supply, and this Russian-Ukraine crisis threatens to disrupt global fertiliser supply significantly.

We predict that this year’s supply will be even worse, making fertiliser scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, which is always vulnerable to these shocks because we are a net importer of the commodity. This will be compounded by the impact of COVID-19 on fertiliser supply, which saw the lowest usage in 2020 because of supply constraints and production bottlenecks from producing companies. COVID-19 Africa Fertiliser Watch Dashboard developed by a partnership between the International Fertiliser Development Centre (IFDC), the African Fertiliser and Agribusiness Partnership (AFAP), Development Gateway, and AFRIQOM (AfricaFertiliser.org) allowed the fertiliser industry to have most ships at sea before the lockdown in 2020, which in a way markedly cushioned the fertiliser sector during the lockdown period.

Fertiliser production and supply will be worse in 2022 than in the COVID-19 era based on the current Russian-Ukrainian crisis and will be further exacerbated by economic sanctions imposed by the EU, NATO, the United States, Germany, and other countries. Crop production and soil improvement in Ghana especially under the planting for food and jobs programme, which rely heavily on inorganic fertilisers, would be severely hit.

Sub-Saharan Africa can boost food production and reduce poverty if fertiliser use is greatly promoted. Ghana has the greatest fertiliser depletion rates in Africa, ranging from 40 to 60 kg of NPK fertiliser per hectare per year (Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 2020). In the southern sector of Ghana, March to May is the main season for crop cultivation, thus fertiliser application is an inevitable and timely supply of the input that will avoid the coming dangers of food shortages in the country.

Policy recommendations to avert potential impacts on food security.

Priority needs to be given to remedying the situation now to avoid a significant output setback in 2022 and 2023. Investing in local production units will protect farmers in the event that critical imports fail to materialise. New fertiliser recommendations and blends for the Guinea Savannah and Forest-Savannah Transition agro-ecological zones by the Soil Research Institute (SRI-CSIR) should have extensive policy support for proper implementation of Integrated Soil Fertility Management with important stakeholder participation.

Additionally, the government must encourage organic fertiliser producers through a purposeful and vigorous local production policy and subsidies to enhance production and protect smallholder farmers. In order for farmers to use local and indigenous methods to re-fertilise their soil, there must be alternatives to inorganic fertilisers such as composting and capacity building in biofertiliser formulation. Livestock and crop farming should be linked so that the livestock and crop farming can coexist, to ensure that the land is fertilised on a year-round basis with organic matter/biofertilisers.

Implement deliberate policies that encourage farmers to grow staple crops (such as millet, maize, beans, groundnuts, yam, and cassava) that require fewer amounts of inorganic fertilisers to grow. COVID-19’s impact on the agrifood sector has resulted in significant production losses, which necessitates urgent action by the government to get additional supplies of fertiliser before planting season especially in the northern parts of the country. Government should provide support to importers to diversify fertiliser sourcing to shore up supply shortfall.

Our policy recommendations for the northern sector.

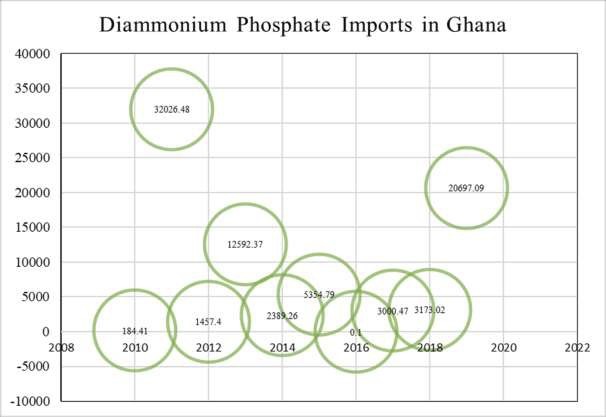

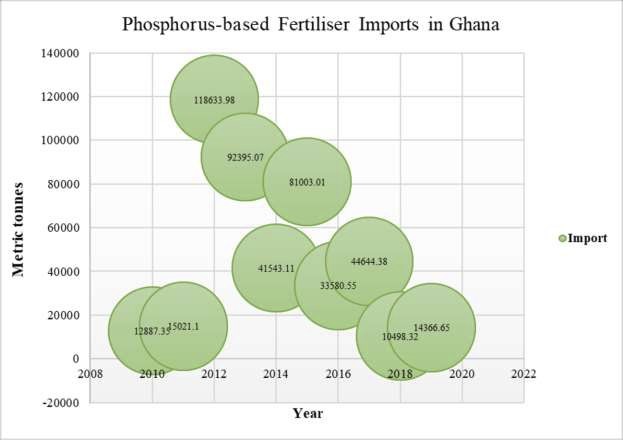

The soils of the Guinea Savanna are infertile. Crop harvesting without replacement has compounded this challenge. However, legumes can access atmospheric nitrogen through symbiotic nitrogen fixation, which can be limited by poor native rhizobia and unavailability of other minerals, particularly phosphorus (O’Hara et al. 2002). Recent studies by Adjei-Nsiah et al. (2018, 2019, and 2021) recommend the adoption and use of different phosphorus-fertiliser blends by farmers as options for grain legume production in the Guinea savanna agro-ecological zone of Ghana.

Climate-smart agronomic practices and phosphorus-efficient cereal and grain legume varieties have been evaluated for use in the Guinea savanna agro-ecological zone by the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture (IITA) and Savanna Agricultural Research Institute (SARI-CSIR). To boost grain legume yields in savanna agro-ecological zones of Ghana, utilising rhizobium inoculants + phosphorus-based fertilisers, cultivating adapted and improved varieties may be the most economically viable and low-risk solutions for our farmers in the five northern regions (Adjei-Nsiah et al. 2018; 2021). Government should consider implementing the fertiliser subsidy policy across board.